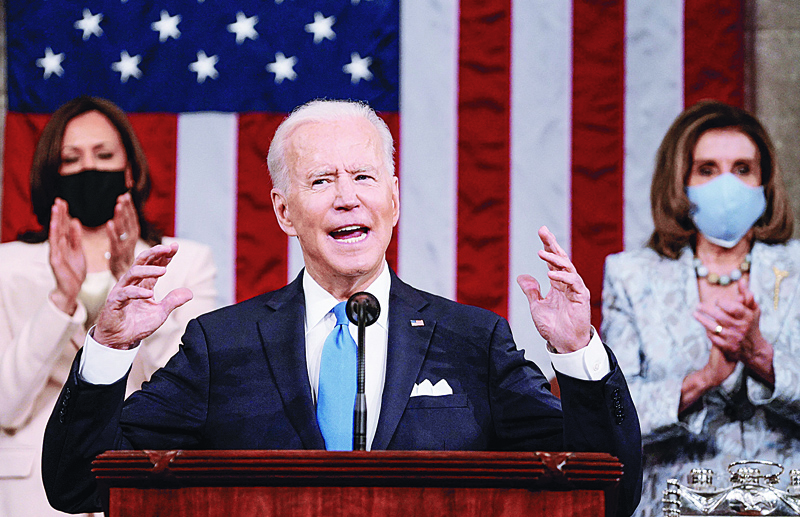

WASHINGTON: US President Joe Biden addresses a joint session of Congress as US Vice President Kamala Harris and US Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi applaud at the US Capitol on Wednesday. – AFP

WASHINGTON: US President Joe Biden addresses a joint session of Congress as US Vice President Kamala Harris and US Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi applaud at the US Capitol on Wednesday. – AFP

PARIS: It's an idea championed by US President Joe Biden, leading economists and even the International Monetary Fund - make the rich pay more taxes to replenish public coffers and narrow huge wealth gaps. Biden wants to end his predecessor Donald Trump's tax cuts for the rich and close what US officials see as loopholes benefiting the wealthiest Americans in order to fund a $1.8 trillion middle-class families spending program.

But even as other governments seek to revive economies pummeled by the coronavirus pandemic, such initiatives would face an uphill battle as tax rates for the rich have been coming down everywhere for the past 40 years. The prominent French economist Thomas Piketty called for a global tax of two percent on all fortunes exceeding €10 million in a column in the newspaper Le Monde earlier this month.

Such a levy would raise €1.0 trillion ($1.2 trillion) per year, Piketty told AFP. He said the funds could be used to narrow the gap between the world's richest and poorest nations since "the sums would be shared among all countries as a proportion of their population."

Tax the rich 'now'

Also this month, Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, professors at the University of California, Berkeley, wrote a column in The Washington Post titled "Don't wait for billionaires to sell their stock. Tax their riches now." The combined fortunes of the 400 richest Americans amount to the equivalent of 18 percent of US gross domestic product, twice the level seen in 2010.

But Jeff Bezos of Amazon, Elon Musk of Tesla, Larry Page of Google and Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook "contribute little to the public coffers", the two Frenchmen wrote. "They structure their affairs so as to have little taxable income," by forgoing huge salaries and holding on to shares in their companies to avoid capital gains taxes, the economists argued.

Saez and Zucman suggest therefore that billionaires should be taxed on "unrealized capital gains" in the form of an exceptional levy that could raise as much as $1.0 trillion. Biden's plan, which he presented in his first speech to Congress on Wednesday evening, would nearly double the capital gains tax to 39.6 percent for households making over $1 million, the top 0.3 percent of Americans. And it would also close what the White House says is a loophole allowing the wealthiest Americans to pass down their accumulated gains to their heirs tax-free.

"How do we pay for my jobs and family plan? I made it clear we can do it without increasing the deficit," Biden told the joint session of Congress. "I will not impose any tax increase on people making less than $400,000. But it's time for corporate America and the wealthiest one percent of Americans to begin to pay their fair share."

Biden has made two proposals to revamp the US economy after the COVID-19 pandemic caused a severe downturn in 2020, the latest of which was the $1.8 trillion American Families Plan unveiled earlier in the day that would pour money into early education, childcare and colleges and universities. The president has also proposed a more than $2 trillion infrastructure plan that would pay for renovating roads and bridges while also funding green technology, expanding broadband internet access and fixing household water supplies.

But unlike the $1.9 trillion pandemic rescue measure he signed last month, Biden is under pressure to find ways to pay for his latest proposals, and in a speech where he called for higher taxes on the rich, the president aimed his rhetoric at the middle class. "I know some of you at home are wondering whether these jobs are for you. So many of the folks I grew up with feel left behind, forgotten in an economy that's rapidly changing," Biden said. "My fellow Americans, trickle-down economics has never worked. It's time to grow the economy from the bottom up and middle-out."

'COVID contribution'

The IMF has backed the idea of raising more revenue from individuals and companies which have thrived during the pandemic. One option would be a "COVID-19 recovery contribution" in the form of a surcharge on the personal or corporate income tax given that some "have done very well and have done very well in terms of stock market valuation," said Vitor Gaspar, head of the IMF's Fiscal Affairs Department, earlier this month.

"There is an opportunity there, and that is one of the options that is on the table," he said while also suggesting closing loopholes in capital income taxation, property taxes and inheritance taxes. In a blog in January, World Bank senior adviser Jim Brumby said most countries are "extremely hesitant" to introduce wealth taxes. "But if ever there were a time that wealth taxes could help, it may be now," he wrote, noting that inequality was "out-of-hand", with the wealthy getting "far wealthier" while COVID-19 pushed 100 million people into poverty.

However, apart from Argentina and Bolivia which have introduced an exceptional "COVID contribution" on large fortunes - purely symbolic in the case of La Paz - few countries seem willing to impose a wealth tax, even in the form of a one-off levy. It is certainly not on the table in Australia, Britain or Germany, even though 54 percent of Britons are in favor, according to a recent poll. France, which eliminated a wealth tax in 2018 after almost three decades, has ruled out fresh hikes.

But not all economists believe a wealth tax is a good idea. Nobel prize-winning economist Angus Deaton told Bloomberg News earlier in April that such a tax would be "very difficult to implement" and give the wealthy "huge incentives to avoid it - and avoid it they will". - AFP