GHARYAN: The Libyan city of Gharyan sculpted a reputation for ceramics generations ago, but fragile demand is forcing potters to seek new markets on Instagram and Facebook. Muayyad Al-Shabani didn't even start out in the craft. He earned a physics degree but struggled to find a job in a country whose economy has been battered by a decade of war and instability since the fall of dictator Muammar Gaddafi.

Then Shabani started, almost by chance four years ago, to sell ceramics online from Gharyan, high in the Nafousa mountains south of Tripoli. Operating out of a Gharyan workshop, his firm with around 10 employees takes orders directly through dedicated Facebook and Instagram pages, packages each item and dispatches them around the world. "First we tried to get ceramics delivered to Libyans living overseas, in the United Kingdom, Germany, the United States, and it was a great success," he said.

"Then we started tackling the problems linked to transport, like a lack of decent packaging. So we invested in packaging machines." The 35-year-old said he wants to stake out a corner on a market with no borders, and compete with products made in China, Turkey and Libya's neighbors. But he knows potters in Gharyan face a competitive disadvantage against rivals from more politically stable countries.

Potteries in Gharyan, a city of 160,000 people, essentially stopped developing in the 1980s and are struggling to keep pace with modernization, he said. Businesses across Libya face daunting logistical challenges and an archaic banking system-a challenge Shabani overcomes by receiving payment through an account in Europe. The money is then withdrawn in cash and delivered to merchants by hand.

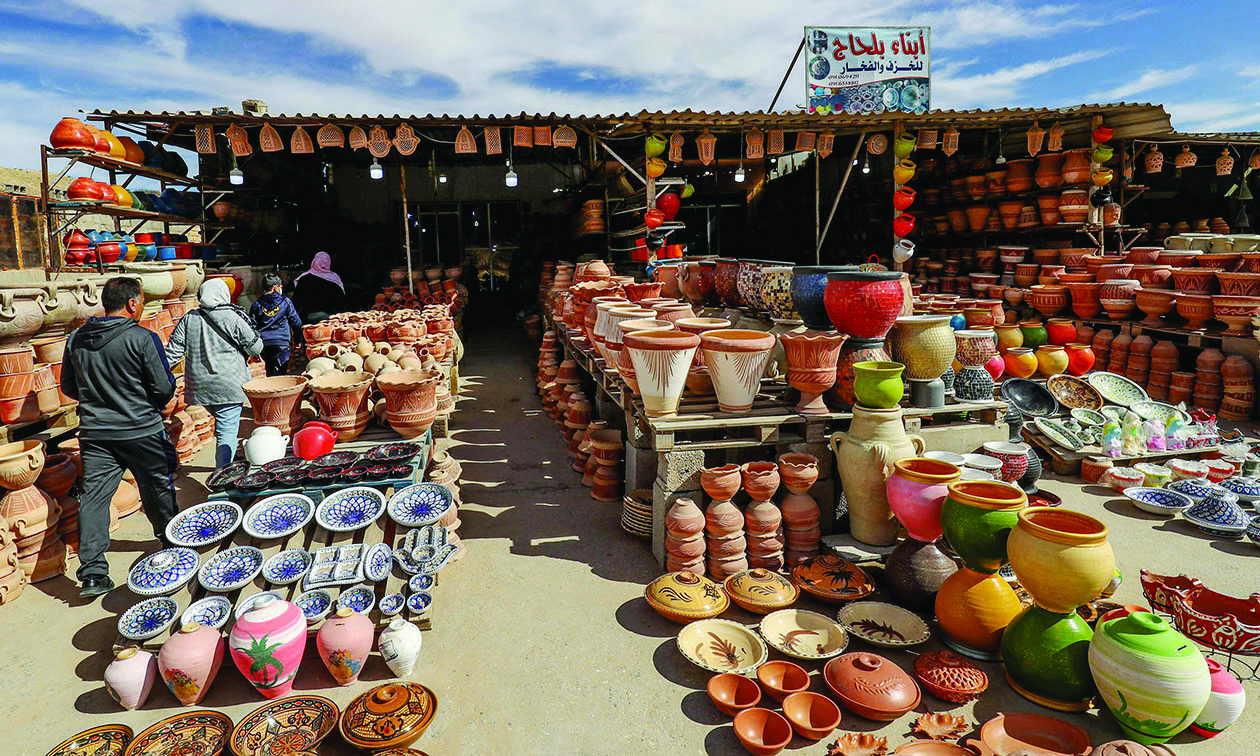

At a neighboring studio, Ali Al-Zarqani would like to move online but is not yet equipped to do so and struggles to reach his markets. Every morning he heads to the family's workshop in the centre of town. The road is lined with shops selling a range of pottery creations-dishes, jugs, pitchers, tajines and flower pots, enameled and hand-decorated with traditional designs. Some display hundreds of earthenware jugs, used for storing olive oil or cool drinking water in the baking Libyan summers.

'Part of our identity'

Zarqani, 47, learned the craft from his father a quarter of a century ago. He starts by crushing and sieving clay-rich earth then kneading it to make it easier to sculpt, before efficiently crafting each piece on his wheel then leaving it to dry for up to 12 hours. Once decorated with natural pigments, the piece is then baked at more than 1,000 degrees Celsius in an electric kiln. "There's a lack of basic materials, which we have to import at high prices, and there are also few workers because of a lack of craft schools," said Zarqani.

"And moreover, demand isn't stable." Still, he hopes "the new generation will take over" to safeguard this "link to our land." Shabani, with his online business, is part of that new era and has found ways around the challenges which have left Gharyan's once-prosperous potteries struggling. He plans to keep expanding. "Ceramics are part of our identity," Zarqani said. "We're attached to it because it represents the identity of Libya."- AFP