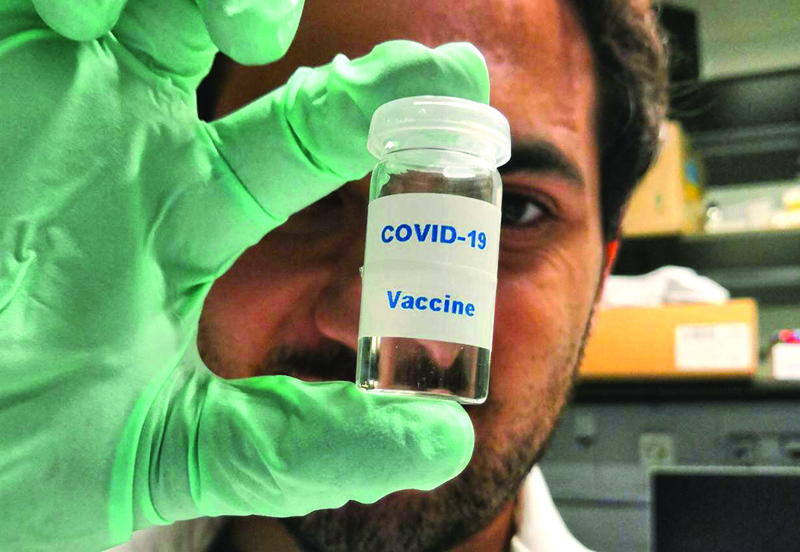

LONDON: Ask scientist Nowras Rahhal about his cutting-edge work on a COVID-19 vaccine and he is eager to explain the complexities, but ask him where he comes from and he struggles for words. Rahhal, who moved to Germany two years ago from Syria's war-shattered capital Damascus, is stateless - meaning no country recognizes him as a citizen. "When you are stateless, the simple question 'Where are you from?' becomes very loaded," he told the Thomson Reuters Foundation. "Most people are happy to say where they belong, but I don't know what to answer. I'd love to have a place to call home."

Rahhal, 27, has just finished working with a team at one of the Max Planck institutes on developing a system allowing a COVID-19 vaccine to be applied to the skin, rather than injected into muscle. He said the technique - targeting specialist immune cells in the skin that can trigger an immune reaction in the body - would require a far smaller dose per person, a big advantage when inoculating large populations.

Before arriving in Germany, Rahhal spent years studying to the sound of bombings and artillery fire, using his phone torch to read when the electricity cut out at his Damascus home. But Rahhal's academic achievements are remarkable for another reason - stateless people often struggle to access education.

'Pure discrimination'

Rahhal's grandfather was among tens of thousands of Palestinians who fled the Mediterranean city of Haifa during conflict surrounding the birth of Israel in 1948. Today there are half a million Palestinians in Syria, but they are not allowed to naturalize even though most were born in the country. Although Rahhal's mother is Syrian, laws in many Arab countries ban women passing their nationality to their children, so Rahhal, his two brothers and sister were born stateless like their father.

There are an estimated 10 million stateless people in the world with large populations in Myanmar, Ivory Coast, Thailand and Dominican Republic. Deprived of basic rights, they often live on the margins of society. While stateless Palestinians do not enjoy the same rights as Syrian nationals, they can access education, healthcare and jobs.

Rahhal, who spent most of his childhood in the now bombed out Damascus suburb of Darayya, went to a school run by UNRWA, the UN agency responsible for Palestinian refugees. The scientist said he was lucky to be born into a family that valued education. His Syrian-born father is an agricultural engineer, his mother an economist. But as he grew up, Rahhal saw how statelessness stalled his father's career and prevented him pursuing opportunities abroad.

There was social prejudice too. After meeting a girl at university, Rahhal was crushed when her family ended the relationship. "They told me I wasn't welcome because I was a stateless refugee. This incident had a big impact on me. It was pure discrimination," he said. Leaving his family in 2018 was heartbreaking. "It was like I was saying goodbye almost for the last time because I don't know when I'll see them again," he said. "When I saw my family crying I was determined to do something that made them proud."

Rahhal said the war has left him with physical and psychological scars, but prefers not to talk about his experiences. He did not flee Syria as a refugee, but applied to study in Germany after gaining a degree in pharmaceutical sciences from Damascus University. Rahhal's diligence has seen him nominated for best international student at the University of Kassel, where he received a masters in nanosciences this month, achieving the highest grade. He has also learned German, worked on cancer drug research and helped with a bilingual storytelling project for refugee children.

'Undefined person'

But Rahhal's statelessness continues to cast a large shadow over his life. Even simple tasks like validating a phone SIM card become a huge headache without a nationality, he said. Flummoxed German authorities have changed his status three times - first categorizing him as stateless, then Syrian, and now as unspecified. "When you look at your ID and you see you are an 'undefined person' it's really painful," he said.

His documents create suspicion among officials and baffle acquaintances. "If I say I'm stateless I worry if people will think I've done something so bad in life that I've had my nationality taken away," he added. Christoph Rademacher, a professor in molecular drug targeting, who picked Rahhal to join the COVID-19 vaccine project, said he was astonished when he learned about the hurdles his protege has had to overcome.

Rahhal is now embarking on a Phd in vaccine technology under Rademacher at the University of Vienna. Their vaccine has passed initial tests and is undergoing further trials with another team. Rahhal hopes his story will encourage other young stateless people to dream big, and spur more countries to back a UN campaign to end statelessness called #Ibelong. UN experts say the global failure to integrate stateless people is an enormous waste of human potential. "I'm very lucky because I had the chance to get an education," Rahhal said. "I'm sure if other stateless kids had these opportunities we'd hear a lot more success stories." - Reuters

.jpg)