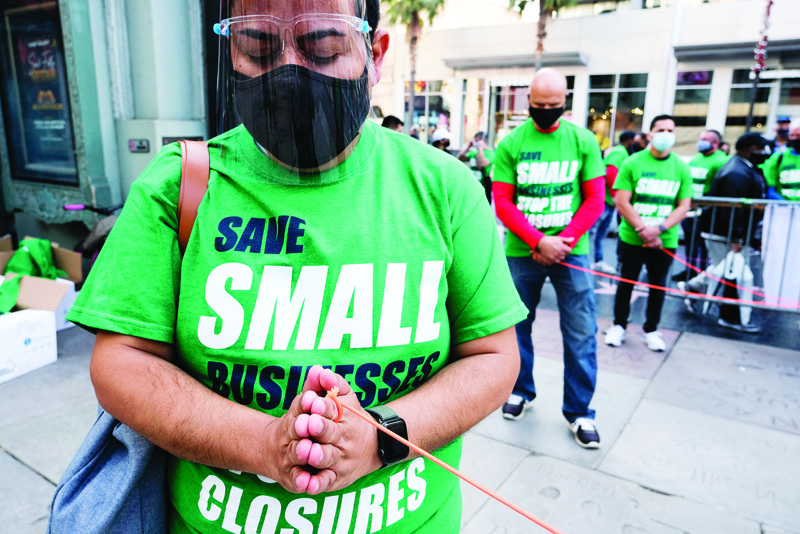

LOS ANGELES: In this file photo members of small business owners practice social distancing in front the TCL Chinese Theatre prior to a 'Save Small Business' protest in Los Angeles, California. Small businesses saw no light at the end of the COVID-19 tunnel as optimism about the US economy waned.-- AFP

LOS ANGELES: In this file photo members of small business owners practice social distancing in front the TCL Chinese Theatre prior to a 'Save Small Business' protest in Los Angeles, California. Small businesses saw no light at the end of the COVID-19 tunnel as optimism about the US economy waned.-- AFPWASHINGTON: Small businesses saw no light at the end of the COVID-19 tunnel as optimism about the US economy waned in January, according to an industry survey released yesterday. Following a third wave of coronavirus cases late last year, and as Congress debates a new round of government aid, the National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB) said its optimism index dropped 0.9 points to 95.0, three points below the average since 1973 and down from 104 in January 2020.

Even as hiring increased solidly, owners expecting better business conditions over the next six months declined seven points to the lowest level since November 2013, NFIB said. January came in with a whimper as consumer spending tailed off sharply at the end of 2020, the report noted. Small firms have benefitted from multiple rounds of government loans, and President Joe Biden's proposed $1.9 trillion rescue package would extend additional aid.

"As Congress debates another stimulus package, small employers welcome any additional relief that will provide a powerful fiscal boost as their expectations for the future are uncertain," NFIB Chief Economist Bill Dunkelberg said in a statement. Ian Shepherdson of Pantheon Macroeconomics notes that the survey-which had just over 1,000 responses-has a "strong Republican bias" and despite the decline had returned to the level seen prior to the 2016 election won by former president Donald Trump.

Spending plan

President Joe Biden's $1.9 trillion proposal aimed at revitalizing the US economy has drawn skepticism from some economists, including a former Treasury secretary who is also a member of his Democratic Party. Larry Summers's warning last week that the plan could cause inflation to rise and crowd out other investment priorities has sparked a debate over whether Biden's proposal is excessive, even for an economy that has sustained massive damage during the pandemic.

Here is a look at the debate over whether the spending package would cause an inflation uptick in the United States:

Summers and Yellen disagree

In a column for The Washington Post last week, Summers, who served as Treasury secretary under president Bill Clinton and as an adviser in Barack Obama's White House, acknowledged that Biden's plan may be just what the economy needs to recover from the sharp growth contraction and mass layoffs caused by Covid-19.

But given the enormous size of the package, he said policymakers should make clear that they will closely monitor for any sustained upticks in inflation, or the increase in the cost of living as measured by commonly used goods and services. He also warned such massive spending could end up leaving the United States without the resources for other Biden administration priorities, like investing the country's aging infrastructure or fighting economic inequality.

Summers' critique was echoed by former IMF chief economist Olivier Blanchard, who said the package is "too much" but could be restrained by new taxes aimed at offsetting its costs and limiting overheating effects. In a weekend interview with CNN, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen acknowledged inflation is "also a risk." But the former Federal Reserve chair said, "We have the tools to deal with that risk," and argued that the president's proposal could get the US economy back to full employment by 2022.

The president's rescue plan would provide for stimulus checks, expanded unemployment benefits and aid to small businesses, though it may ultimately get whittled down from its initial $1.9 trillion price tag as it makes its way through Congress, where his Democratic party has a slim majority in both houses. If passed, the measure would be the third major aid package approved by Congress, following the $2.2 trillion CARES Act enacted as the pandemic struck last March, and a $900 billion follow-up measure passed in December.

Those have been credited with help keeping the country from a worse economic downturn, but as of mid-January, more than 17.8 million people remain unemployed and nearly four million have left the workforce entirely, and their prospects for returning to work are widely seen as depending on how quickly the virus can be tamed. "Even if there is an approved recovery plan, we will still be in an environment where not everyone will have jobs," Gregory Daco of Oxford Economics said in an interview.

Inflation today

Inflation is tracked by the US Labor Department's Consumer Price Index (CPI), which crashed as the pandemic arrived, then staged a partial recovery through the rest of 2020. By year's end, it had climbed 1.4 percent overall, less than the 2.3 percent increase seen in 2019, and well below the central bank's 2.0 percent goal. However the stimulus bills plus the Federal Reserve's move to cut interest rates to zero have helped some sectors of the economy recover faster, Daco said, pointing to home construction, where prices have risen.

A similar dynamic may play out across the entire economy as the pandemic abates, causing a spike in inflation, but Daco does not believe the price hikes would be permanent. "After the rebound, there will be a lull. Once conditions return to 'normal' there will be no reason for prices to increase on a lasting basis," he said.

Fighting inflation

The US economy has not experienced sustained high inflation for decades, said Jonathan Millar, director of US Economic Research at Barclays Investment Bank. He credited that to changes in the global economy that have led to more competition holding down prices, along with more effective monetary policy from the Fed.

The central bank has only a few tools to fight economic slumps, cutting interest rates being one of them, Millar said. But when it comes to fighting inflation, it is much better equipped. "I'm sure you've heard the phrase in the debates... 'it's much better to do too much than too little,'" he said. "It's actually very supportive for the Fed. They have the tools to deal with that inflation." - AFP