ARBIL: Growing up in Iraq, Omar Farhadi would heat up dinner for his Jewish neighbors when they rested on the Sabbath. Few are left, and their heritage risks fading away too. Across Iraq, Jewish roots run deep: Abraham was born in Ur in the southern plains, and the Babylonian Talmud, the central text of Judaism, was compiled in the town of the same name in the present-day Arab state. Jews once comprised 40 percent of Baghdad's population, according to a 1917 Ottoman census.

But after the creation of the Israeli state in 1948, regional tensions skyrocketed and anti-Semitic campaigns took hold, pushing most of Iraq's Jews to flee. In the north, the Kurdish regional capital of Arbil was once the heart of the ancient kingdom of Adiabene, which converted to Judaism in the 1st century and helped fund the building of the Temple of Jerusalem. Today, Iraqis have fond memories of Jewish friends and neighbors, including 82-year-old Farhadi, whose father owned a shop in a Jewish-majority district of Arbil.

Farhadi himself had several Jewish classmates at school and learnt English from a Jewish teacher, Benhaz Isra Salim. "One day in early 1950, Professor Benhaz came to say goodbye to our Arabic teacher. They hugged and began to cry because Benhaz was travelling to Israel," he recalled. "All of us students started to cry as well. That was the end of Jews in Arbil."

Fading ties

The roughly 150,000 Jews still in Iraq in 1948 fled fast: by 1951, 96 percent were gone. Staying meant defying growing discrimination and property expropriation. Following the US-led invasion of 2003, some Jews were flown to Israel on special evacuation flights while others left during the ensuing years of sectarian warfare. By 2009, there were only eight Jews left in Baghdad, according to diplomatic cables published by Wikileaks. The internecine violence did not grip the Kurdish region. A 2015 law in the zone recognised Judaism as a protected religion and created an official representative, a post now held by 58-year-old Sherko Abdallah.

The law, and the lack of sectarian bloodshed in the zone, created an environment of "more coexistence" compared to federally-run areas in the south, he told AFP. Still, of the estimated 400 families of Jewish descent in the Kurdish zone, some have converted to Islam in recent years. "Most others practice in secret, because admitting you're Jewish is still a sensitive issue in Iraq," said Abdallah, adding that his "connections" within the Muslim-majority community had helped keep him safe.

A real sense of identity, however, was still missing. He applied for official permission to build a Jewish community centre but had not received official approval. "I want a Jewish leader to come teach us the proper customs, but that's not possible under the current conditions," Abdallah added. And the link between the few families left and the roughly 219,000 Jews of Iraqi origins in Israel - the largest contingent from Asian origins - is fraying. "Now, the Iraqi Jews who left to Israel in the 1950s still find ways back into the Kurdish region with their Iraqi ID cards," Abdallah said. "But within five years, they will pass away and the whole relationship will be severed."

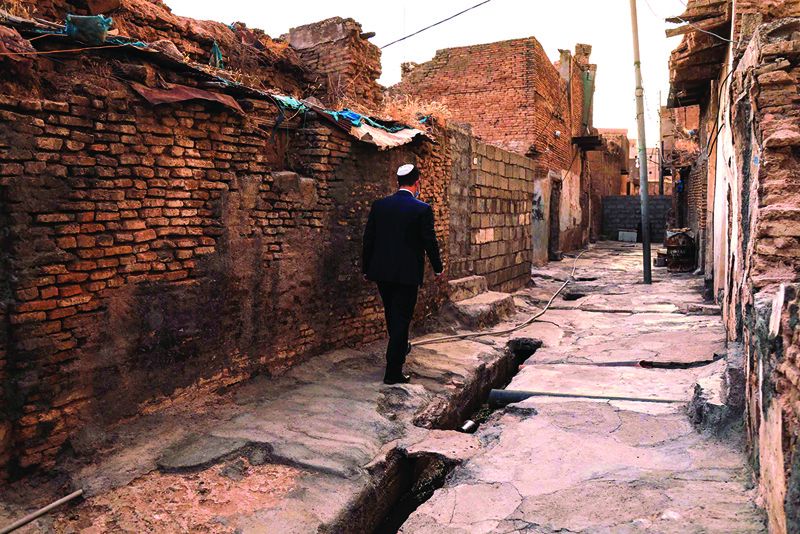

History in ruins

There is already little to see. Many Jewish homes were seized by the Iraqi state before 2003, and Jewish schools, shops and synagogues across the country are mostly crumbling from lack of maintenance. In the north, heritage is faring slightly better. Arbil's Museum of Education, housed in the city's oldest primary school, includes a room dedicated to Daniel Kassab, a well-known Jewish Kurdish art teacher and painter. Residents of Halabja, Zakho, Koysinjaq and other parts of Kurdistan still refer to old "Jewish neighbourhoods" when giving directions in their hometowns.